On Drowning

We used to go to Montreal for long weekends, shooting straight up the Northway from Albany and finding ourselves, four hours later, in an actual foreign country. One September, we saw Tim Raines at the end of his illustrious speed demon career hit a line drive double to right field in an Expos 4-2 win over the Phillies, play by play in French. We were delirious, despite the anemic size of the crowd and the reprehensible astroturf. That night, we ate a tajine that made us weep for joy and the following day, a Saturday, we explored the Arab quarter around Rue St. Denis and bought our own clay pot so we could recreate the flavor of North Africa in the Berkshires. Montreal felt so international, so open. In an Ethiopian diner where we went for lunch before making the return trip south, a waitress demonstrated the proper method for eating the spongy bread called injera by tearing a piece off the aluminum tray on our table with her hand and stuffing it directly into my mouth. We were lit up when we arrived home late in the evening of September 9, 2001.

Now, these neighborhoods and similar areas in London, not to mention Paris and Brussels, seem filled with threat. I am not speaking here of the low probability of being caught in the crossfire or the eurocentric concern about bombings in familiar places as against the same bombings in Iraq or Pakistan. I'm not speaking about the origins of radical Islam or the role of the West in aggravating Muslim grievances. I am speaking about that fear that has grown in us over the last several years and the fact that my sense of who I am is offended by this fear. What happened to the person who cherished and defended the idea of a common humanity? Was this person an artifact of a period when the official enemy was summed up by the vaudeville clown Khrushchev banging his shoe at the U.N.? The cognitive dissonance gives me a headache and the headache has gotten worse.

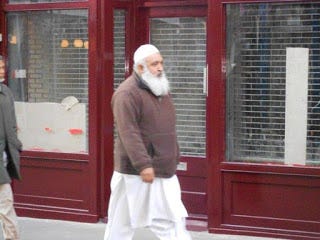

It was only five years ago that we spent an afternoon meandering around Brick Lane in east London, inhaling the fragrance of curry and zatar, admiring the Indian women in their pink and green silk saris and the Muslim men in their loose white kaftans and taquiahs, indistinguishable to me from the

kippot worn in synagogue. We were such innocents abroad that we walked up to a group of these men, standing outside of a small mosque, and asked if we could go inside and look around. You know, like tourists. One man asked, "are you Muslim?"

No, I am not. I am an older American Jewish woman living in a tranquil preserve in western Massachusetts, far from the current suffering, far from the bombed out wreckage of Aleppo, far from the capsized boats crammed with smuggled refugees drowning in the Adriatic. We have seen these pictures, but we have also been assaulted by a constant barrage of fear-mongering images and rhetoric, not only from the usual suspects, but from the empire of entertainment. We have been

homelanded.

This year, as I prepare for Passover, my teeth are on edge, filled to capacity with a volatile amalgam of anxiety and sorrow. I consider what it meant to be stranger in the land of Egypt, what it meant to be enslaved. I picture the Israelites, desperate to be free, rushing toward the sea and the sea in its turn swallowing the pursuing Egyptians. It is an accident of history that those of us gathering for seders in the carpeted comfort and apparent safety of our homes, time zones away from the bloodshed, only imagine that we are drowning in our own anguish. It could be otherwise. Sometimes, the sea doesn't part and the drowning is real.

This Passover, may we keep our heads above water so that we can be grateful for the goodness of our lives, the idle ballpark days and memorable meals and, at the same time, help one another develop the capacity to witness the terrible upheaval of humanity all over the world that understandably frightens us and rightly breaks our hearts.

Please share seventysomething with your friends.

aleph.org/civicrm/contribute/transact?reset=1&id=28