I was not a born reader. We were a word-obsessed family but our love of language took the form of bloodthirsty competition, not slithering off into a corner to fondle books in private. We were avid puzzlers and fierce Scrabble players, but my mother’s reading was limited to Ellery Queen and the other crime fiction of the day and my father was mostly a New York Post kind of guy. Words and reading seemed to be two different fields of interest, as if those strings of letters lining up side by side had a life of their own and did not exist for any larger purpose. My mother thought it was important to develop a taste for reading, but then she felt the same way about tennis and ice skating.

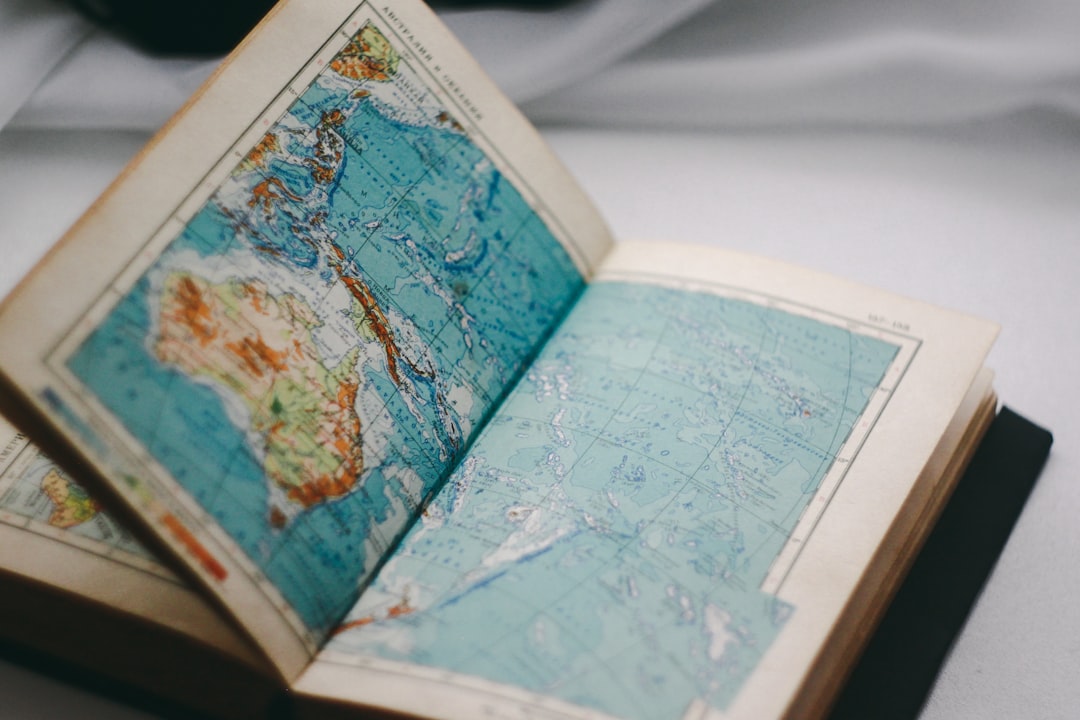

The only books I remember being intimate with as a child were a history of the American presidents and a world atlas, both oversized volumes with brittle, yellowing pages. The first featured an engraving of each President, John Tyler, Warren Harding and so on on the left and a biographical sketch on the right…..Tippecanoe, Teapot Dome whatever. Both books were from the ‘30s, so the Presidents ended with FDR of blessed memory and the atlas contained places like Formosa. They transmitted a kind of documentary history to me when I looked at them over and over in the early ‘50s, releasing their dust into the upholstery. They supplemented the formal education I was subjected to in the local public school, all spelling lists and chief exports of Argentina. I did not seemed to know about imaginative literature.

I don’t think I got any closer to the alchemy of story as I labored through Silas Marner in high school. It wasn’t until college when I crossed paths with Mrs. Dalloway that I discovered that there were people called novelists who descended into the feeling lives of characters of their own invention and revealed something you could learn about life that you couldn’t get from an atlas. Nothing could be more transgressive when you think about it. Here was a person, Woolf, Nabokov, who moved into the attic of another person’s mental house and started rifling through their dreams and old photos. Once you’re in that cobwebby space, anything can happen. Memories, anxieties strange preoccupations can rise to the surface and take on a life of their own. Gogol’s nose starts walking down the street.

A political tract sets its intention and goes about its business trying to convince the reader of some point of view. The reader will either buy it or not. But fiction, in its effect, is as unpredictable as any game of chance. The mind of the writer as it bleeds out through the wounds of the characters stains the shirt of the reader. Sometimes the stain comes out in the wash, sometimes its indelible. There’s no knowing what it will do and there’s no controlling it, which is why authoritarians of all stripes have always been afraid of literature. Some people, thinking of Huckleberry Finn as an invading army, react with their own brand of violence. Violence against the spirit, like banning books and suffocating the minds of schoolchildren in Tampa and Tehran. This is its own kind of invasion. When I read about book banning in Florida, where old women wiggle their toes in the sand and old men play pinochle in Miami Beach, where kids line up for the cotton candy in Orlando, my stomach tightens up, my breath becomes shallow. I feel as if my viability as a life form is suddenly in question. How could I survive without books?

This is because once I found them some sixty years ago, I discovered that books were my ticket out of a necessarily narrow life, the limits imposed by my being American, Jewish, female, white, middle-class. I have not lived in the social confines of the czarist countryside, but I’ve read Chekhov. I have not spent a day in William Kennedy’s crime-infested Irish Albany, but I’ve read Billy Phelan’s Greatest Game and it never leaves me. It’s not the specific content of these books that makes them transgressive. It’s the expansion of human consciousness that results from reading them that worries the book banners. They want to keep us small. They want to keep our imaginations imprisoned, out of the library, into Disneyland.

*************************************************************************************************************

On Sunday, March 26th, paid subscribers will have access to our new monthly feature, Many Voices. The special guest for March will be the poet Marjorie Power. Marjorie has published four collections and numerous chapbooks. To read more about Marjorie Power and her poetry, visit www.marjoriepowerpoet.com.

Please consider upgrading to paid to support seventysomething and become a contributor to and a reader of Many Voices.

*************************************************************************************************************

I’m also pleased to invite you to a service at the Unitarian Universalist church in Housatonic, Massachusetts where I will be offering a sermon via zoom on March 12th. If you are in the Berkshires, please join me for the hour-long service beginning at 10:30 am. The sermon is entitled “Remembering What We’ve Always Known.” You can also email me at seventysomething9@gmail.com for the zoom link.

Copies of my 2019 essay collection, Twilight Time: Aging in Amazement, are available directly from me (signed) or from Amazon or your local bookseller.

It’s very encouraging to hear from you.

Thank you, Susie, for saying what needs to be said.