On the way home from the cemetery, a crispy early November graveside service witnessed by a flock of beloved contemporaries, I stopped at Tractor Supply to buy a chanukah gift for my grandson. I was standing on line, surrounded by wire fencing and chicken feed under the harsh fluorescent glare, when an ancient man, practically a fossil, paid for a fifty pound bag of something. Then I got involved with my plastic and my receipt and didn’t see the hunched over old guy shuffle out of the store. In the parking lot, I found him standing between a shopping cart and the open trunk of his car looking puzzled and apprehensive. Hey, I said, that looks heavy. How about you and I lift that thing together? You know, one on each end? I expected him to decline the offer of help from a famously puny 76-year-old woman. He did not. He grabbed one end of the fifty pounder. I grabbed the other end and we hoisted that sucker into the trunk. Lifting the bag lifted my spirits.

This man was probably not that much older than I am. Maybe ten years. But in the collected folklore of my imagination, he was The Grandfather, my grandfather. I never had one. I always wanted to and you can’t buy a grandfather at Tractor Supply. I thought, when I was a little girl, he would have brought me Tootsie Rolls and a baby doll that cried when you squeezed its tummy. He would have told me what I needed to know about the old country, about Romania in the 19th century. My father’s father, born in Budapest, died in 1935, very long ago for sure. But he left a boatload of children, my Rosenberg aunts and uncles, a bangled and boisterous group sustained by pastry. There was enough of him in their sugary flesh to foster the fantasy that I knew him. My Romanian grandfather, Louis Jerchower, on the other hand, remains a cipher. He died in New York in 1924 after various bankruptcies and at least one episode of white-collar crime wherein Jerchower Brothers allegedly sold merchandise made by prison labor, apparently a no-no. I spoke recently with my cousin in Teaneck to ask if he was sitting on any further details. He said that whenever he asked his father about grandpa, Uncle Jerry would evade the question and refer to Louis as The Black Sheep of the Family. Still, Jerry gave his only son the updated American name Lewis in memory of our grandfather. Just saying those two words “our grandfather” accelerates my heart rate. I don’t know if he was a Black Sheep, but he is certainly a Lost Lamb.

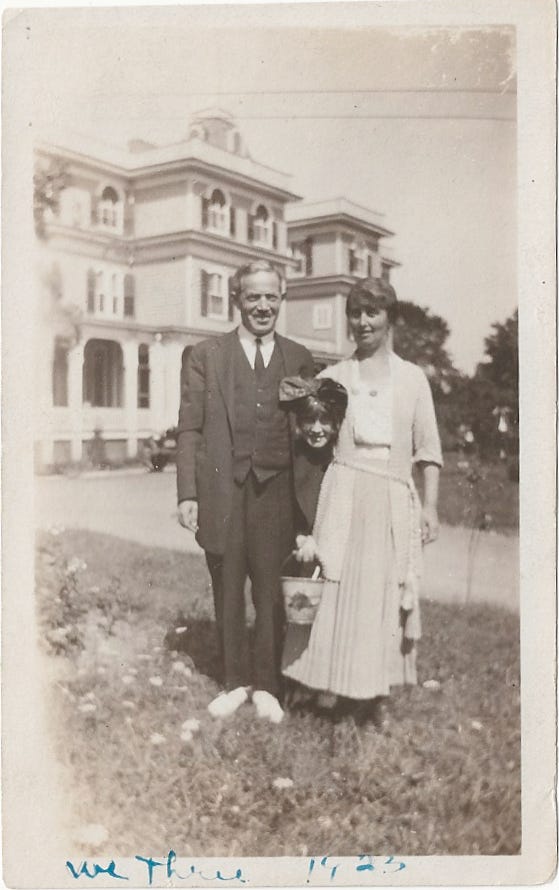

Here he is a year before his death with my grandmother Anna and my mother playing a game of “everything is alright,” he in his white shoes and my mother with that ridiculous bow.

She even labelled the photograph “we three.” I cringe when I read those words in her familiar handwriting. Are they ironic? It is the only existing image of Grandpa Louis.

I am incomplete without him. I reach for him, but he’s not there. Like the ten years before I was a born when my immediate family consisted of my mother, my father and my much older sister, there are blank spaces, erasures in the tape. In the corner of my life story where a grandfather is supposed to be, feet up on a needlepoint hassock, there is nothing, a black hole. Only the whiff of failure and a metastatic rage left behind by years of dependency on his rich brother-in-law, Joseph. I have a vague notion that Louis ended up collecting rents in tenements owned by Joseph, but I may have made that up. I may have needed to dramatize his despair. All I really know is that my mother always said her father was “very stern” when I tried to bring his image into sharper focus. I once asked if he every beat her or grandma. She denied it, but she was clearly afraid of him. There is a story she once told, but later forgot, that as a child clearing the table, she dropped a stack of dishes and fainted out of fear. What is it like to be afraid of your father? What is it like when he dies at fifty-two and everyone sweeps him under the Persian rug and never mentions his name again?

Signed copies of my 2019 essay collection Twilight Time: Aging in Amazement are available directly from me. The book can also be ordered from Amazon or your local bookseller.

Hi Jan. Working on the dashboard problem.

Sometimes the relatives of our imaginations are more alive for us than the ones we actually experienced! Thanks, Susie.