This is the fourth in an occasional series of conversations with artists on the rich subject of the interface of Art and Spirituality.

Rosemary Starace first encountered her artistic vocation before she even started school—and is grateful that school did not entirely destroy her imagination! In her teens, she saw the connection between art and soul (or “psyche”) and began what became a lifelong devotion to the study of art-making, depth psychology, and the sacred. Her path has taken her deep into Jungian thought, the Taoist and Zen poetry of ancient China, as well as her own creative practice. She has a master’s degree in the Creative Process in the Arts. In addition to making art and poems, she also writes essays that muse on the process and purposes of art. Her work is online at www.rosemarystarace.com.

When I engage with Rosemary Starace, a writer and visual artist living in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, she is always in motion and at the same time always entirely still. For better than forty years, Rosemary has gifted us with drawings, paintings, constructions, collages, and artworks that defy category. The volume of her work and the range of her materials is stunning. Still, there is something quiet, something at rest at the heart of it. The focus of Rosemary’s art has always been the inner life, no matter the variety of images and media. Her concerns come back again and again to questions of exile and belonging, shattering and connection. Her creative process often involves the collection of discarded or “low” materials which are then repurposed and given new life. There is power and healing in reassembling what has been torn apart.

Although I had seen fragments of Rosemary’s work over the years in the Berkshires, her 2019 show In-Dwelling at the Oxbow Gallery, then in Northampton and now in Easthampton, MA, unleashed a flood of sympathy and recognition in me. I understood that she was sitting at the table eating dinner with us in all our struggles and inviting us to join her from outside our thinking selves. This installation of two and three-dimensional houses made largely from cardboard and other throwaway, intentionally impermanent materials, explored the fragility of shelters. The shelters are both those built to serve as places of refuge for the body and the body itself in its provisional nature, its vulnerability. In her artist’s statement for the show, Rosemary writes “I started these sculptural houses in response to the plight of refugees and they became an homage to our universal quest for sanctuary and safety. Houses, bodies, civilization — our whole human endeavor is so rickety. Like these houses, we are beauties made from refuse and paint and cardboard, always on the way to dust.”

What is the role of vulnerability and impermanence in your art-making?

Well, we are vulnerable and mortal—it’s the human condition. Making art is a response to, a reckoning with that. It asks about the meaning and purpose of our lives on earth; it can engage us with the mystery and fascination of being. What can we intuit, what can we know? Can these explorations of mine provide consolation or guidance for others? Or solidarity in our shared circumstances?

For the In-Dwelling show you wrote, “A sadness slipped into some of these works, a sadness that hungers for the solace and beauty of the natural world and faces the calamitous upheaval and potential destruction of all that once seemed dependable and abiding.” Recognition of the calamitous upheaval has impacted everything, our seeing and feeling, our working and loving.

It certainly has. My hope is always that making art will help to clarify for myself and others what is beautiful and worthy of love and attention.

Continuing the conversation about impermanence in art and life, what is the identification of “low” or found materials, scraps and leftovers…with the inner life?

I like low materials because they are cheap and plentiful—and therefore encourage risk-taking—and because I find them inherently beautiful and satisfying to work with. (When I was making the little dresses, I was so struck by the lovely drape and diaphanous quality of the plastic bags!) I also came to love that these materials are humble and unprepossessing, and that they don’t last. I question sometimes why I work with materials that are ephemeral. It’s a built-in obsolescence! But, as I touched on before, I see it as a way to engage with my own and others’ ultimate smallness and impermanence. And to keep my focus on the redemptive, connective, exploratory act of art-making rather than the very much less important effort of creating a monument.

It’s a kind of reclamation project, isn’t it? You are the savior of unwanted objects and materials which, when gathered together into new combinations, are born again.

I like that reading of it! Yes, I’m reclaiming the inherent beauty and sufficiency of what appears to be lowly and unneeded. And, so as not to sound like I have this all figured out, I do this because I need to reclaim these qualities in and for myself.

In your current work you have turned to collage. Is this reclamation how you envision collaging?

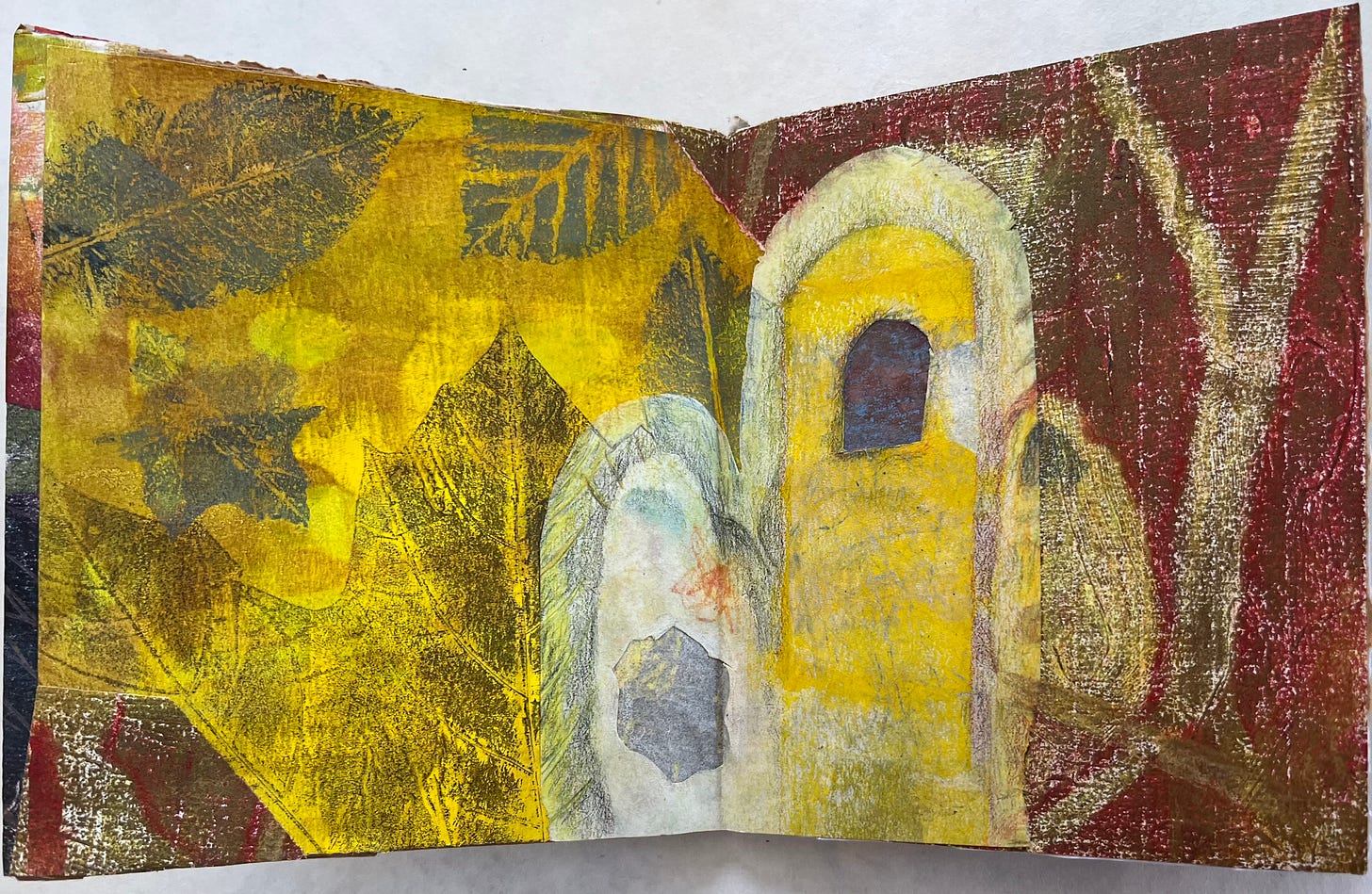

Yes, I’m collaging in the pages of books I made from paper bags saved from grocery deliveries during Covid! The collage materials are mostly scraps of things I made, either intentionally (old drawings, monoprints, and doodles) or unintentionally (marks made cleaning off a brush or a brayer). Occasionally, I use found images, too. Some of these images arise from dreams or look like dreams—fragmented, mysterious, maybe unfathomable. The book form is fun to work with—like a shelter for these vulnerable pieces. Once again, my desire is to make beauty and wholeness out of what has been separate. That does seem to be the metaphor of collage: a little ritual of making connections and transforming the given materials.

During the last year, after suffering the loss of my partner, I am soothed by this practice of bringing scattered pieces together, giving them new form, and pasting them down (semi) permanently. Working with scraps and leftovers is also a way to interact with chance and open myself to gifts that don’t come from my thinking mind. It’s a practice of surrendering to something greater than myself, a need that has come marching forward during this time of grief and change.

But beyond the pleasures of re-making and “fixing” what has been scattered, there is also the tremendous satisfaction of tearing these old things up in the first place! I’m seeing the collage process more broadly as ritual that attempts to deal with randomness. I take the raw material of my life and act like a god upon it, tearing it asunder and then putting it back together—ta-da!

It’s like a child’s game invented to gain mastery over things beyond her control. I am reminded of a game my stepson made up and repeated over and over when he was a toddler. His mother (with whom he lived most of the time) went back to work, and this was a big disruption in his life. During that period, he had discovered a low cabinet in our kitchen that was mostly empty. And he would dive into it shouting “Gots to go to work!” He’d pull the door behind him and there would be several seconds of silence. Then he would burst out and yell, “I’m home!”

All the activities and rituals I’ve described are my personal tasks, impossible ones, like the ones in fairy tales. All night, all day, I seem to have to be there, sorting out the flecks of gold, bringing back the dead, returning to myself. Weaving and unweaving and reweaving. But these are also humanity’s tasks, and I want my work to also be an invitation for others to engage with the mystery and mayhem of existence.

It is extraordinary to be greeted by Susie's words and be given the opportunity to explore the vast realms of Rosemary's art process. Her creative or life process. The "finished" art pieces are magical in their beauty and surprising complexity.